The Art and Science of Financial Planning

My most recent FP Collective article discussed an ideal setup for the savings and investment accounts of spouses/common-law partners. I posted that article in the thread that had inspired it in the FPAC discussion forums, and I got some very thoughtful comments back. In this article, I’m going to explore the process of finding the ideal overlap between the quantitative and qualitative elements of the financial planning process.

I’ll not do the comments justice here (you should really join FPAC and read the forum posts for yourself), but the gist is roughly that:

There are valid reasons for one spouse or both to have accounts to which their spouse does not have access.

· Those reasons can range from the positive (spouses want gifts to one another to remain a surprise) to the empowering (a spouse with an account in their own name has a degree of financial empowerment) to the difficult (a spouse in an abusive relationship will have a harder time leaving if they don’t have some money in their own name).

· The financial planner has an obligation to understand the dynamics in a relationship before making recommendations.

· There are no ‘one-size-fits-all’ recommendations.

I agree with all these points. This is where we must distinguish between the best financial planning recommendation and the best financial recommendation for the situation.

As financial planners, we have an obligation

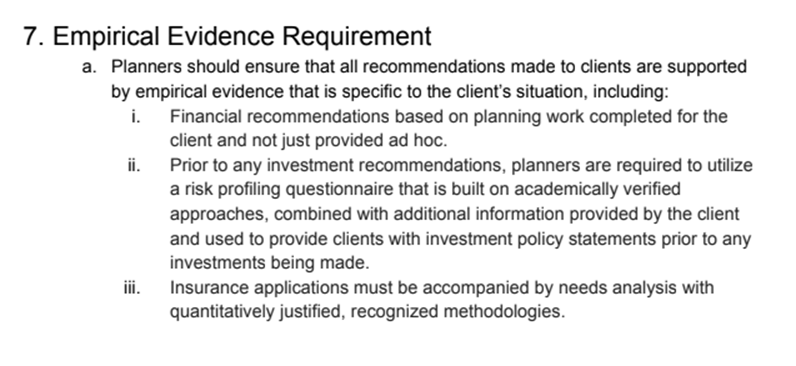

(From the FPAC Charter):

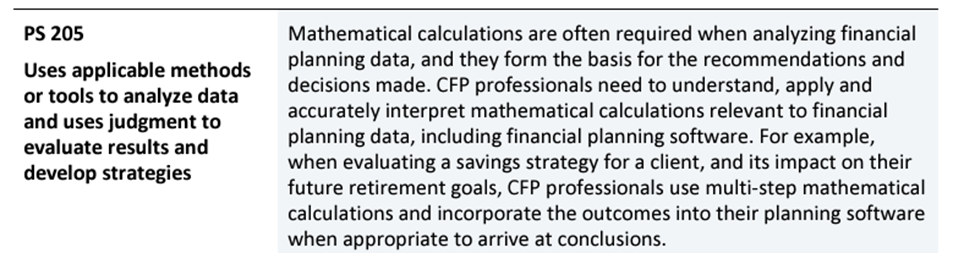

(From FP Canada’s Competency Profile):

to understand what the best recommendation is for a situation. That means running as much math as is practical for the situation and understanding how the math points to the best recommendation. Let’s consider this the quantitatively optimum solution. This is the science of financial planning.

That quantitatively optimum solution may, however, not be the best solution for the client. This is where the financial planner must understand a wide range of qualitative factors to help the client make the best possible decision for their circumstances.

Some of the factors that might provide a valid justification for not implementing the quantitatively optimal solution could include:

· Family and couple dynamics. Some examples of this are described above.

· Client financial literacy and capacity. A Holdco or a trust might be ideal for a client, but if the client doesn’t understand enough about those solutions, an interim solution might be appropriate while the planner helps the client develop capacity.

· Capacity to implement solutions. A planner might identify 10 or 12 things that would improve a client’s financial life, but it’s generally only practical to implement 1-3 solutions at a time.

This is far from an exhaustive list; the point is that the best financial plans will find the middle ground between the quantitative and qualitative. I would argue this is the art of financial planning.

An overly strong reliance on the ‘art’ cannot, however, become a fallback for lazy planning. A planner who implements halfway solutions for a client and never seeks to improve on those solutions has likely not lived up to the best interest standard that is owed to clients.

Consider the example of permanent life insurance. I know it’s common when a planner asks a client to discuss their estate objectives, the client will answer something to the effect of ‘to minimize taxes’ or ‘avoid probate.’ These answers often fall on the heels of a planner discussing terminal taxes and probate fees. I would suggest that framing this conversation differently might lead to clients suggesting 'I want my kids to continue to get along after I am gone.’ I would wager that most families would gladly pay more tax if they knew it was going to keep relationships intact.

If the planner simply takes the client’s estate planning answer at face value, they are likely to implement a permanent insurance solution and consider their job done.

The planner who can look forward to working on the relationship further and fully unpacking the qualitative elements that are truly important to the client might recognize that a term insurance solution is likely to meet a client’s needs for the time being and can be converted later to permanent insurance if necessary.

But that necessity should only be considered to have arisen once the planner has had a chance to more fully develop the client relationship. That includes both education delivered by the planner and giving the client more opportunity to discuss what is important to them, beyond the purely quantitative.

There are many other examples in financial planning where we can take a ‘do-no-harm’ approach and give room for a client to have the opportunity to properly explore what matters to them. Consider:

· Taking less investment risk than our formal processes suggest until we have some confidence that we have correctly assessed the client’s risk characteristics.

· Converting group life insurance on departure from employment until we know what the results of underwriting an individually underwritten product will be.

· Getting a client who doesn’t want to spend a few thousand dollars on wills and powers of attorney to use one of the digital estate tools that are now widely available.

In all these cases, the short-term solution gives the client optionality later on to explore the solution that turns out to be optimal for them.

I believe that a successful financial planning relationship is one where the planner helps the client to make the optimal decision. This requires that the planner understand both the quantitatively optimal solution, and the qualitative factors that make this client who they are.

Discussion