RDSP Part II: Accumulation

In my last article, we covered the general scope of the RDSP. In this article, we will look at the accumulation of funds in the plan.

Before we do that, a quick recap of the major purposes of the RDSP:

· It’s a retirement account.

· It’s not designed to solve short-term financial concerns.

· It can be funded with a generous allocation of government grants and bonds.

· It is (outside of Quebec) designed not to interfere with provincial disability supports programs.

The criteria to open an RDSP are that:

· The plan beneficiary has access to the Disability Tax Credit. This is also a requirement for continued contributions.

· The plan beneficiary is a resident of Canada. Again, this is a requirement for continued contributions.

· The plan beneficiary cannot be age 60 or older.

The RDSP can accrue value in five different ways:

· Contributions. Anybody can contribute to an RDSP. The lifetime maximum is $200,000 of contributions. There is no annual maximum, though we will explore some circumstances where practical concerns might limit contributions. Like other amounts connected to the RDSP, the $200,000 can be traced back to 2008, the first year for the plan, with no adjustment for inflation since then.

· Grants. The Canada Disability Savings Grant is often promoted as the primary reason to set these plans up. We’ll fully explore the matching available in this article. It’s very common that the CDSG forms the bulk of assets in an RDSP in the first few years after the plan is established.

· Bonds. The Canada Disability Savings Bond is available for lower income households with an RDSP. Because they are not matched, CDSB funds can accrue in an RDSP even where a family has no funds otherwise to start a plan. In addition, through an arrangement with Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) financial institutions will deposit the first $50 into a new RDSP where funds are not otherwise available, allowing the plan to come into existence and attract bonds.

· Registered Plan Rollovers. Funds can roll into an RDSP from an RESP, RRSP, RRIF, LIF, or LIRA, or their provincial equivalents. The rules around these rollovers are quite restrictive. We’ll examine them more in Part IV of this series.

· Investment Returns. Funds held in the RDSP should be invested. Investment returns within the RDSP grow on a tax-deferred basis. Higher-income families might even consider the RDSP as a form of income splitting, as it’s normal to see a high-earning parent fund a plan for a lower-earning child with a disability. The plan beneficiary will ultimately be taxed on the investment gains. We’ll examine investing in the RDSP further in Part VIII of this series.

The focus of this article will be on the grants and bonds.

The first thing we need to do is understand Adjusted Net Family Income. This is a common measure when determining eligibility for programs defined in the Income Tax Act. There are 2 separate circumstances we are concerned with:

· A minor child’s AFNI will comprise their income and any caregiving parent’s income. In the case of a minor child residing with both biological parents, all 3 persons’ incomes must be considered.

· An adult’s (starting the year the individual turns 19) AFNI is their own income, plus a spouse’s income, plus any minor children in that person’s care.

Net income refers to Line 23600 income (total income minus deductions from income) for each person. In most households, Line 23600 income will comprise all employment, investment, and net self-employment income, reduced by deductions for RRSP and pension contributions, child care expenses, premiums for the CPP enhancements, and the very limited set of other deductions available to most households.[1]

Access to grants and bonds is income-tested. No grants or bonds can be paid once the plan beneficiary is age 50 or older. Even if that person would retroactively qualify based on prior years of eligibility, once a plan beneficiary marks their 50th birthday, no grants or bonds are payable.

Grants are paid at one of two rates:

· Lower earning households generate a 300% grant on the first $500 contributed, and a 200% grant on the next $1,000. For a single year of RDSP participation, then, a $1,500 contribution can attract $3,500 of grants.

o It is possible to buy back earlier, missed years. If the person with the disability has been disabled (that is, had, or retroactively has, access to DTC) for prior years, grants can be retroactively paid up to 10 years back, to a maximum of $10,500 for a single year. Current year grants are always paid first, followed by any prior missed 300% periods, followed by any missed 200% periods.

· Higher earning households generate a 100% grant on a $1,000 contribution. Again, it is possible to buy back these grants a maximum of 10 years back, and to a cumulative total of $10,500 of grants paid in a single year.

The lifetime maximum grant one can receive is $70,000, which is 20 years at the high rate of matching.

CRA sends a letter each March or thereabouts to any RDSP beneficiary detailing the amounts available through grant buybacks.

Canada Disability Savings Bond eligibility is very similar. Again, we’ll look at AFNI two years back. If AFNI is greater than the amount where the first Canada Child Benefit reduction threshold starts, then the bond will be reduced accordingly. For 2025, that threshold is $37,487. The bond will be gradually reduced until income hits $57,375, at which point it becomes unavailable. (The rate of clawback is $.05 per dollar of income.)

Bonds can also be acquired retroactively if the person with the disability is deemed to have been eligible for the Disability Tax Credit in earlier years, or was eligible for the DTC. Bonds can be generated for up to 10 years, retroactively. Again, this is based on an income test for each specific year where the bond might apply.

The lifetime maximum bond one can receive is $20,000, which is 20 years of bonds at the maximum rate.

The income test here is based on AFNI for the relevant set of income earners 2 years prior. Eligibility for grants in 2025 is determined based on comparing 2023’s net incomes to the sum total of the bottom 2 tax brackets from 2023. If income is below that threshold, then the high rate of grants is available.

For recent years, the AFNI cutoff (looking at the income 2 years prior, but the cutoff figure for the current year) is:

· 2023: $106,717

· 2024: $111,733

· 2025: $114,750

Some planning opportunities may present themselves. Let’s look briefly at a funding example.

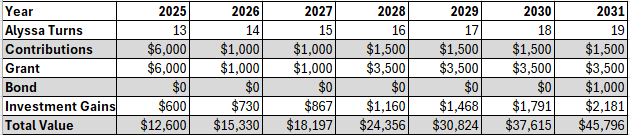

· 2025: In 2025, Nelson and Zoey get a diagnosis for their daughter, Alyssa. Alyssa is 12 at the beginning of 2025 and will turn 13 during the year.

o Alyssa’s physician files a Disability Tax Credit form indicating that Alyssa has been disabled since the 2020 tax year, meaning 5 full years of grants are available.

o Beyond the scope of this discussion, 6 years of Disability Tax Credit (out of a maximum of 10) are paid to Nelson and Zoey, covering the years 2020 to 2025, inclusive.

o Their 2023 household income was over $120,000 per year; that year’s threshold was $106,717. The same is true for 2018 (the relevant year for 2020’s grants) through to 2022 (the relevant year for 2024’s grants). This year, they contribute $6,000, attracting $6,000 of grants for the years 2020 to 2025 inclusive.

· 2026: Their financial planner looks at their situation and helps them engage in some tax planning. Zoey reduces the income she’s taking from her corporation, and they move from using TFSAs as their primary investments to using RRSPs, creating additional tax deductions. For 2026, they can keep their combined incomes below the 300/200% threshold. This will allow them to qualify for the higher levels of grants in 2028. Beyond that, they just contribute $1,000 to Alyssa’s RDSP in 2026, the year Alyssa will turn 14.

· 2027: This year, Alyssa will turn 15. They engage in the same tax planning as the prior year. They contribute $1,000 to her RDSP, attracting a 100% matched grant based on their 2025 incomes.

· 2028: The year Alyssa will turn 16, they contribute $1,500 and get $3,500 of grants, based on having kept their 2026 income low. They continue to tax plan to keep net income low.

· 2029: Alyssa will turn 17 this year. Their 2027 income will allow them to contribute $1,500 to Alyssa’s RDSP and obtain the 300%/200% matching grants. In 2031, Alyssa will be 19, and her income will be used to determine CDSG eligibility. Because of the 2-year income lookback, it no longer benefits Nelson and Zoey to try to keep their income low to help Alyssa qualify for grants.

· 2030: This is the last year when Nelson and Zoey’s income will impact Alyssa’s eligibility for grants and bonds. Alyssa will turn 18 this year. Grants are provided at the 300%/200% level.

· 2031: Her parents have contributed $12,500 to her RDSP and the government has contributed $18,500. At a modest 5% return, her RDSP will have approximately $37,615 in it at the start of 2031. The $12,500 of investment by Nelson and Zoey has generated an IRR of 26.4%. This year, assuming Alyssa doesn’t end up with some very surprising sources of income, Nelson and Zoey will contribute $1,500 to her RDSP, attracting $3,500 of grants, based on her 2029 income falling below the threshold. She still has $51,500 of lifetime grants available. It’s also most likely that this will be Alyssa’s first year to receive the Canada Disability Savings Bond. If this is all true, by the end of 2031, the RDSP will have $45,796 in it, representing an IRR of 24.8%.

These contributions, grants, and returns, are shown on the table below:

Understanding the CDSG and CDSB and how they are calculated can help the financial planner optimize both savings strategies and tax planning for a family using the RDSP. We’ll see throughout this series that the RDSP provides a variety of planning opportunities for the planner willing to put the work in.

References:

[1] Most of the tax savings measures typically used by families (base CPP and EI premiums; medical expenses; charitable contributions) are tax credits and have no impact on net income.

Discussion