RDSP Decumulation Part III B

The primary intended use of the RDSP is like the RRSP – it’s a retirement plan. There are some differences. The RDSP has mandatory withdrawals (LDAPs) starting the year the plan beneficiary turns 60.

My previous article explored the foundational rules for RDSP withdrawals. It may be worth reviewing that article before starting into this one.

Lifetime Disability Assistance Payment

The primary intended use of the RDSP is like the RRSP – it’s a retirement plan. There are some differences. The RDSP has mandatory withdrawals (LDAPs) starting the year the plan beneficiary turns 60. There is only one LDAP withdrawal formula – any additional withdrawals being sought in retirement will require a DAP.

There is no AHA applicable to LDAP withdrawals.

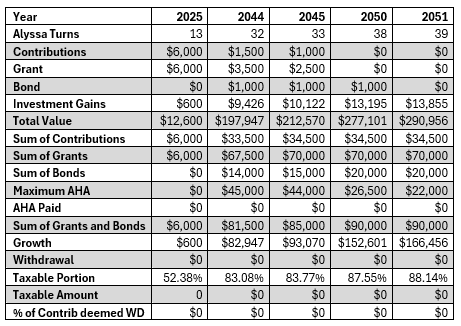

Alyssa will start her LDAP in the year she turns 60. Assuming her parents only fund the RDSP to the extent needed to optimize for grants, they will continue to fund $1,500 per year until the year she turns 32, with a final $1,000 contribution in the year she turns 33. She will have received the full $70,000 of grants by that time. Her bonds will stop being paid in the year she turns 38, when she will have received the full $20,000. By that year, the account has a balance of $277,101, with just $34,500 of principal contributed. This is all done using a steady 5% rate of return.

This also assumes that Alyssa never has great income. If she can earn a meaningful income, she will still qualify for the CDSG at the lower 100% matching, and there will be some value to the plan. But it will be needed less than it would if she were unable to earn meaningful amounts of income.

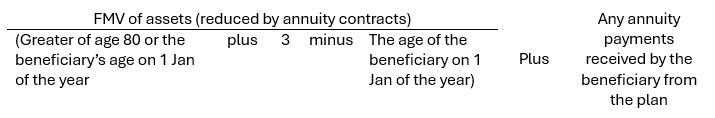

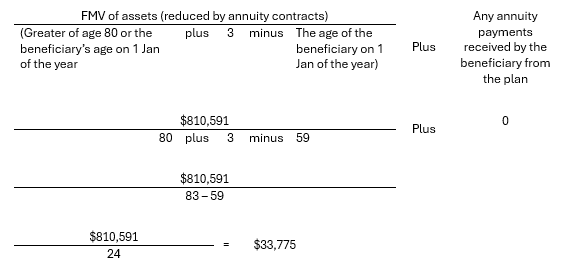

By the year she turns 60, the plan will have a balance of $810,591. The withdrawal formula kicks in that year:

The formula refers to annuity payments. It is possible to purchase an annuity (though no annuity with any possibility of a benefit paid to a survivor, a topic we will cover later in this series) with RDSP funds. Any annuity payments made from the RDSP are added to the LDAP formula, which is similar to annuitizing a portion of a RRIF.

We can then have a look at some representative years. The first 5 years described below show the start of the plan, the accumulation of grants and bonds, and the final grant and bond payments.

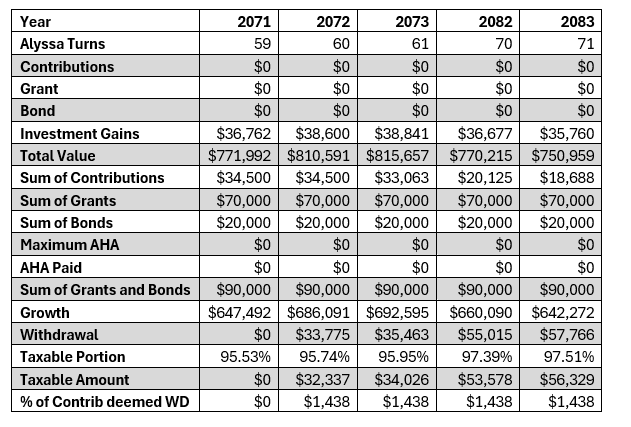

The next 5 years shown below describe the year prior to the start of the LDAP period, the first year of LDAP payments, the year following, and the state of the plan 10 years after the LDAP period begins.

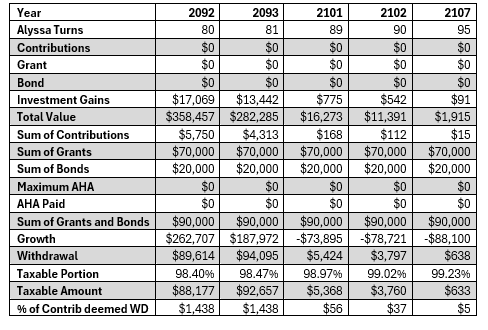

Finally, we can see the period 20 years after the LDAP starts, and the last years of the plan. Assuming only LDAP withdrawals, the plan effectively runs out of money in Alyssa’s early 90s.

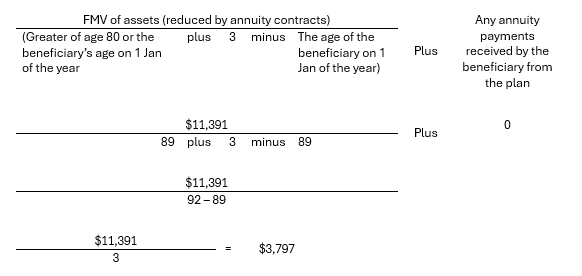

We can apply the formula described above to a couple representative years, just to see how it works.

The year in which Alyssa will turn 60:

The year in which Alyssa will turn 90:

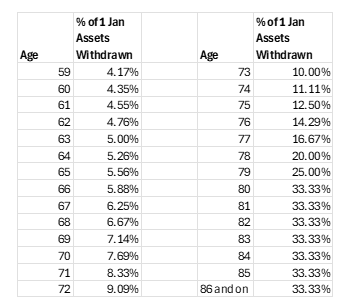

The plan is effectively designed to provide income at roughly 4-10% of the total assets from age 60 to 80, but then to see the level of assets drop off quickly thereafter. We’ll see in a future article that an RDSP isn’t a great estate asset, so there is some logic to this setup.

It’s common to see a table of RRIF minimum withdrawals by age, but I can’t recall seeing a similar table for LDAP withdrawals. As such, here is a table showing LDAP minimums by age:

This varies by province, but in most provinces, provincial disability supports cut off at either age 60 or 65, so the RDSP/LDAP steps in when needed. A well-funded LDAP like this one is likely to put Alyssa in a better financial position than she’s ever been in.

While the LDAP formula is a bit complicated, those who are familiar with the RRIF will at least be on familiar terrain. Alyssa’s RDSP will provide a steady amount of income, most of it taxable, through her retirement years.

In the next instalment in this series, we'll cover decumulation using the Specified Disability Savings Plan.

Discussion