Myth: Investing is About 'Winning'

The spring is a busy time in the wide world of sports with the month of May beginning with both Kentucky Derby and the French Open – not at all timely for a post in the summer, but we’ll run with it anyway.

Two vastly different sporting events, a horse race on one hand and tennis on the other. Each game employs a different strategy for success which is actually the opposite of each other when we zoom out.

Horseracing is what would be called a ‘winners’ game – where the fastest horse will win more times than not, all else being equal. Oversimplified: breed the fastest horse = win the most races.

Tennis is different. For the amateur player, simply returning the ball over the net more than three times in a rally is enough to win the majority of points and matches. Effectively, in amateur tennis, waiting for the opponent to make a mistake is enough to increase your probability of winning.

Tennis can be though of as a ‘losers’ game – where more points are lost by action than are actually ‘won’. Said another way – the winning strategy is one that is focused on not losing. Charles D. Ellis has been writing about this in his book “Winning the Loser’s Game: Timeless Strategies for Successful Investing” which has held the test of time, and is now is in its 8th edition.

The finance world is built around breeding the fastest horse. It makes sense when you think of how much money is poured into the business in hopes of finding an edge. The slightest edge could change lives – and could be very profitable for both the investors in the promise of higher risk adjusted returns and the firm who can then market such returns and attract more clients.

I have sat through thousands of investor presentations, mostly from people incredibly well researched, highly intelligent, and passionate about their work.

How is that working for everyone?

Not great.

When we peel back the curtain of the industry, we find investment managers often try to breed the fastest horse or ‘hit the winning shot’ so to speak. They want to find the ‘next big opportunity’ or to ‘cut ties with a loser’ – meanwhile – the winning strategy might be as simple as returning the ball over the net so to speak. That is – allow others to attempt the ‘winning shot’ and instead simply do the simple thing and return the ball over the net.

Readers will recognize this as “action bias” – our human need to ‘do something to fix’ this. It serves us very well in most things in life – just not investing.

In most cases, mutual funds as a whole underperform their benchmarks over the short-term, and increasingly so over longer periods.

Where it gets difficult is that the ones that do outperform over a 1- or 3-year period may do so quite handily even. This is simply the law of numbers – someone somewhere is going to do it.

Think about what we said before – about the potential for investors getting higher returns and the firm going out and marketing this. This is saying the quiet part loud so here goes – the finance industry has done market research and overwhelmingly the top thing that attracts fresh new clients is the promise of higher returns. What most marketing-based firms do next is take those glorious 3-year performance numbers on the road, advertisements in elevators, billboards, commercials, you name it.

Like clockwork – the money flows.

This same thing plays out in the top institutions – think the people who allocate money for pension funds or university endowments – they are all victims of the same tendencies to try to find the winning investment, and extrapolating past performance into the future.

The top investment managers – the kinds we’re all out here trying to identify ahead of time (think ‘hitting the winning shot’) all have to be unique enough in their process to outperform – ie. they can’t do what everyone else is doing if everyone else isn’t beating the index anyway. Also true is that they have to be unique enough that they will underperform, and often do.

The trouble is that even the most knowledgeable investors – the people running those pension funds and endowments have a problem. State Street surveyed people responsible for overseeing these pools of money and found ‘…that 89% of these executives would not tolerate underperformance for more than two years before seeking replacement’ (source: State Street Global Advisors, 2016. Building Bridges: Are Investors Ready for Lower Growth for Longer? How Are They Working to Bridge the Performance Gap? Boston, Mass.: State Street Corporation).

If the best managers underperform so frequently, and the majority of knowledgeable investment allocators have such short time horizons, how many good managers are fired during unlucky times, and how many bad managers are hired after very lucky times? If they can’t stand underperformance, they’re again looking backwards and buying into recent outperformers on the eve of the replacements potentially cooling off.

Realistically, the conversation goes like this 99% of the time:

Client: ‘Should we make any changes to the portfolio?’

Advisor: ‘well, we could sell that and buy this?’

Client: ‘has it done better than what we’re selling?’

Advisor: ‘of course, over the last 3 years it’s done better by __%, it’s a 5-star fund and a good investment’

Client: ‘ok, you’re the expert’

The issue that this creates is a never-ending cycle – the next 3 years, or better yet the next 30+ years which corresponds to most people’s retirement horizon will have a new batch of out-performing 5-star funds, and those that were the top funds likely aren’t included anymore.

This is how the wealth management industry was built – they know that that people know that better returns are appealing. They also know that that line they use ‘Past performance doesn’t mean future performance’ is as ignored as the speed limit on the Autobahn.

The winning shot sells.

It makes sense – as humans we like to know we’re making smart decisions. It’s only natural that our instincts in investing are to align ourselves with what has been working.

As investors, both amateur and professional, we are bound by an underlying desire to get ahead, innovate, and use our wits to achieve our goals faster and easier.

We are not racehorses. Subtle decisions that we use to try to ‘win’ are often the exact things that slow us down.

After a tennis match, the players meet and shake hands. The one who lost thinks ‘if a couple tough breaks went the other way, I would have one, next time will be different’.

Investment allocators do the same, it sounds like ‘I was right, the markets are wrong’ or something like that.

Like tennis, investing is a losers game – keep things simple, return the ball over the net so to speak, and identify the ‘fear of missing out’ or ‘fix what’s clearly broken’ subconscious feelings ingrained in us all.

It will feel awkward at the time, but as they say – to be right for the right reasons in the long-term, we must also be willing to be wrong for the right reasons in the short term.

As we read articles in the media or communications from an advisor, ask, is the speaker:

- Prognosticating about the markets?

- Talking about short-term strategies for investments in long-term buckets?

- Playing a ‘winners’ or a ‘losers’ game?

- Will this help me achieve my goals?

People never want to ‘buy high and sell low’. When we hear that expression, people often think of selling during a sizable downturn. Equally important are the smaller decisions to buy or sell. Minor as they are, these ‘winner’s game’ decisions add up over time.

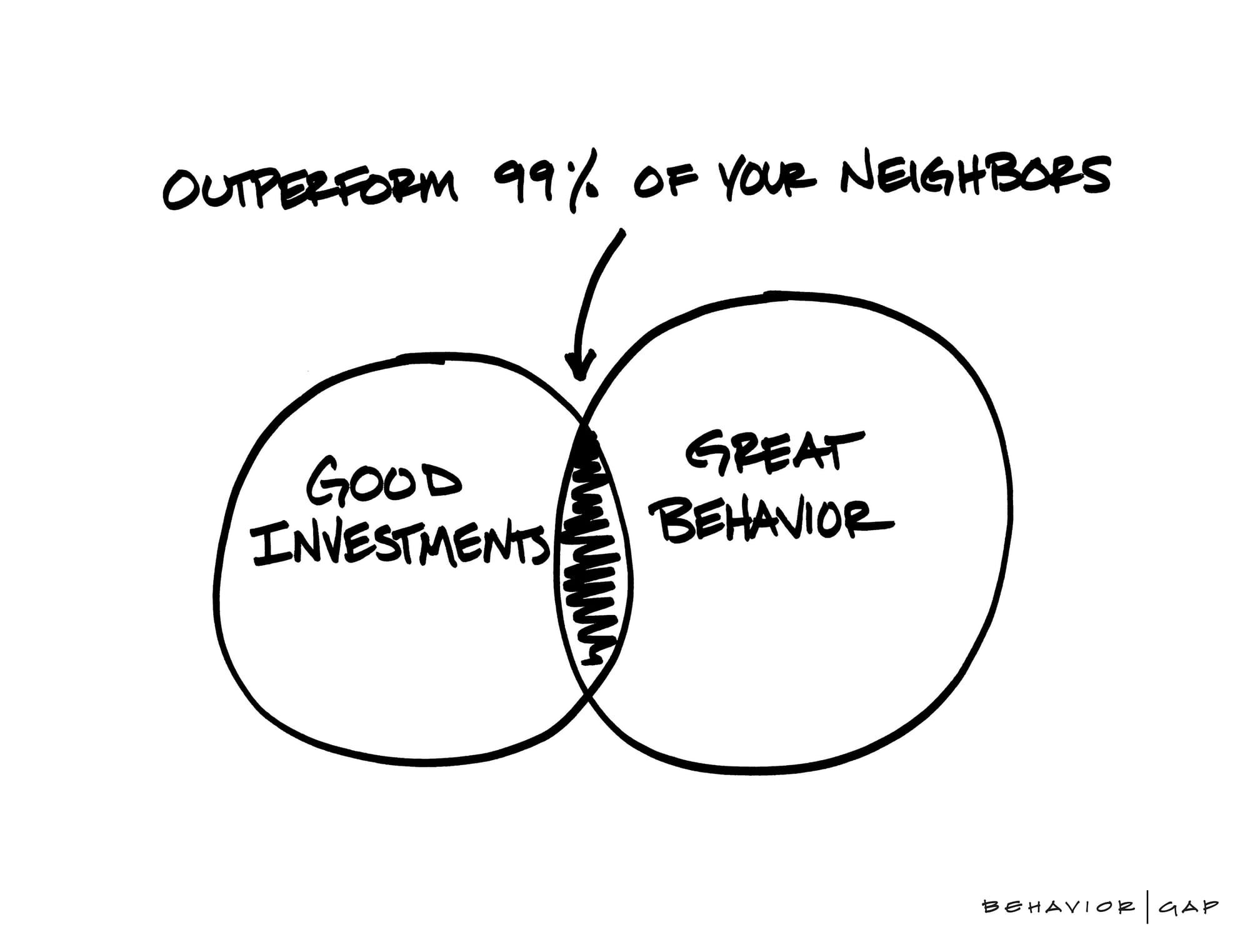

Great behaviour with good investments helps investors more than great investments with poor behaviors and incremental decisions.

Discussion