LTD Claims Part I: Parties to the Lawsuit

I’ve previously written here about the value of my membership in Canadian Group Insurance Brokers (CGIB). This is where I get pretty much all of my group benefits-related learning, and it’s a great community.

Recently, Dave Patriarche, the captain of the CGIB ship, posted an interesting summary of a lawsuit in the benefits space. This lawsuit presents a lot of very useful information for the financial planning community.

I’m going to break my analysis of this lawsuit down into three articles. In the first, I’ll describe the parties to an LTD contract, and how they might incur liability. In the second, I’ll explore relevant financial planning concerns. In the third, I’ll explore the composition of group benefits premiums.

The full text of the lawsuit can be accessed here.

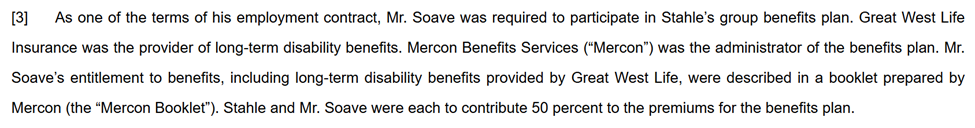

Let’s start with a look at what we know about plan design, from the text of the lawsuit:

“Required to Participate”

First, the plan featured mandatory participation. Not all plans do this. Some plans feature optional participation, but this creates a lot of risk for an employer. If the employer allows an optional participation plan, and an employee opts out, and then has a disability or premature death or travel insurance claim, there will be questions about how the employer communicated to the employee. Did the employer give the employee the opportunity to join the plan? Was there some lost communication between the parties? This is a regular enough source of liability that a lot of group benefits advisors won’t work with groups who want optional enrolment plans.

With mandatory plans, it’s common that the ‘risk’ elements of the plan are mandatory, but the health and dental portion may be optional if there is proof of spousal coverage available. I would suggest that, despite the perception of plan members, it’s the Long-Term Disability (LTD) and travel insurance portions of the plan, along with possibly prescription drugs, that provide the greatest degree of risk management. Regular health and dental benefits are really a tax and budgeting play, but not a risk management tool. The life insurance provided in group benefits plans is usually far less than what is needed and can create a false sense of security.

The Parties to the Plan

Mr. Soave is an employee of Stahle Construction Inc. The employment agreement (whether there is a written agreement or not, there is always an employment agreement, even if it’s just the default provided under provincial employment legislation) is between these two parties. Stahle agreed to provide benefits to Mr. Soave. It’s the content of that agreement that forms much of the content of this lawsuit.

The insurer provides benefits to Stahle. There is a master contract between those two parties, and that master contract dictates the insurer’s obligations.

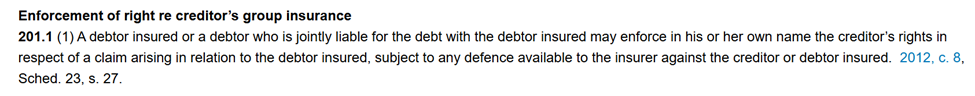

This is where group benefits gets a bit murky. If Mr. Soave has a claim, he is now dealing with Great West Life (GWL). GWL now has obligations directly to Mr. Soave. Even though there is no contractual relationship, there is language in the provincial insurance acts that bypasses the lack of a contract between these two. The legal concept here is ‘privity of contract’, and if you’re a fan of Bob and Doug Mackenzie, this real-life lawsuit might sound familiar. The relevant portion of the Ontario Insurance Act reads:

You might notice that the benefits administrator is also mentioned. Mercon specializes in administering benefits plans for the construction industry and trades. They were likely the plan broker as well.

At the risk of oversimplifying:

· If there is some question about whether the terms of Mr. Soave’s employment do or don’t give access to the benefits plan, that’s likely a matter between him and Stahle.

· If, once Mr. Soave has a claim, GWL treats him badly (doesn’t pay a valid claim or denies the claim for specious reasons) that’s likely a matter between him and GWL.

· If GWL doesn’t live up to its contractual obligations to Stahle, such as regularly not processing employee claims, that could be a matter between GWL and Stahle.

· If Mercon promised something to Stahle as part of their sales and marketing (e.g. “100% of claims paid”) and that ends up not being true, that’s likely a matter between Stahle and Mercon, though it could also present problems for the Mercon-GWL relationship.

It might be worth noting that, strictly speaking, we should be talking about the ‘plan sponsor’ (employer in this case) and ‘plan member’ (employee in this case). Not all group benefits contracts are employer-employee agreements, but that’s the case here, so that’s the language we’ll use.

The Booklet

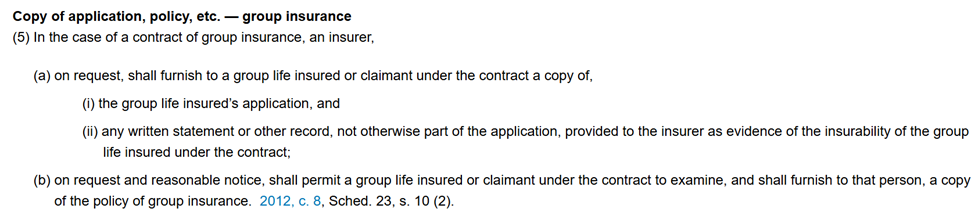

This is a recurring issue in group benefits. The Master Contract (between GWL and Stahle) is a hefty document that generally includes proprietary information about Stahle’s business. It’s simply not practical to make the Master Contract available to employees. That said, Ontario includes language in its Insurance Act that gives an employee the right to “[T]he policy of group insurance”:

Because the employee doesn’t generally have access to the Master Contract, the benefits booklet becomes their go-to for information about the plan. It’s unfortunately very common for the language between the two documents to be inconsistent. Paper benefits booklets are becoming increasingly rare, and many benefits booklets are behind corporate firewalls today. This presents a problem for financial planners who are trying to help their clients navigate their insurance needs.

Premium Structure

The plan here calls for a 50/50 contribution of premiums, which isn’t necessarily going to lead to the best outcomes. But we’ll leave that aside for a future article.

Summary

It's useful to understand the relationships between the parties in a group insurance contract. This is not necessarily intuitive. As we'll see in the next article, understanding these relationships can lead to better outcomes for all parties.

Discussion